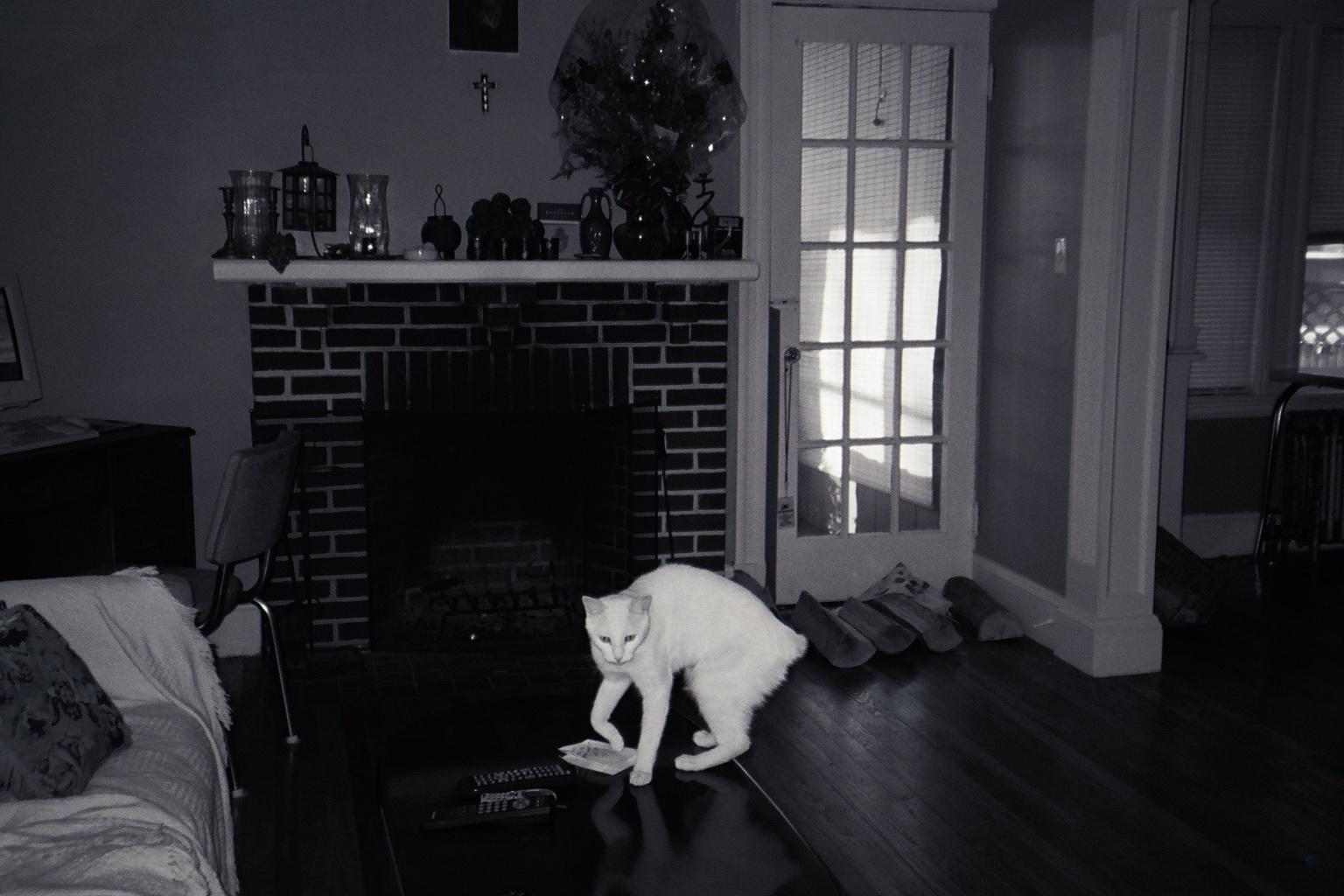

Photo: Maria McCarthy Qtip

THE LIFE OF RILEY

by Deidre Woollard

Riley and I connect because we are both connoisseurs of the futile. I learn this about him on our first date when he tells me how he used to dig pools in the desert—swimming pools for racehorses in the Saudi Arabian desert. You can’t get more pointless than that. Riley tells me this as a prelude to the meat of the story, his years in a Saudi Arabian prison.

I don't know if the story is true, nor do I care. We’re drinking down at the Silver Shamrock. He’s about four Guinnesses in. I’m lagging a cider or two behind but the room has already begun to assume the hazy glow I associate with drunkenness.

“They left me there to die in that prison,” Riley says earnestly, taking one of my hands in his workman’s mitts. “I had only a thin sheet to cover me scorching limbs.” His bloodshot blue eyes fill with tears. I’m suddenly very conscious of the fact that I am dating a six foot two inch Irish hunk who is sobbing in a bar. Bobby, the bartender, looms in the corner and raises an eyebrow at me, ready to move in if I need help. I wave him off with my free hand. I can handle this one.

“It must have been terrible,” I say, letting my hand rest a moment on his knee.

“It was,” he answers, suddenly brightening, “but I wrote a song about it. Would you like to hear it?”

Next thing you know Riley has commandeered the small stage from the somnambulant cover band in the corner who were playing a rather lackluster version of Pretty Woman. Riley takes guitar in hand and plays. None of his songs seem to be about Saudi Arabian prisons; in fact, I think I’ve heard all these songs before, these sad Irish songs of love and loss. He gets the whole bar singing along in a drunken yet heartfelt rendition of Danny Boy.

That night, I take him home to bed with me. We fall into my sheets in a boozy tumble. He leaves nearly immediately afterward. He says he will call and I immediately school myself not to care. Nonetheless, I am pleased to hear his rushed Irish brogue on my answering machine the next evening.

I’m a responsible woman by day. These nights are my reward for a life spent carrying water in a sieve. My penchant for futility manifests itself in the feline. I’m a cat veterinarian for the local shelters. Shots and neuterings and spayings, countless ear infections, I clean them up as much as I can and hope for the best. But there are always more cats than owners, and so I do that job too. I send them to sleep with something that feels like kindness.

We try hard to find them homes. The shelter staff and I concoct charming stories and names for them. We run their pictures in the newspapers and on the local television stations. The worst cases come home with me. Right now I live with Seymour, a Maine Coon cat with retinal atrophy and stomach-emptying disorder, which means he is a longhaired blind cat who throws up a lot—an impossible sell. I also have Margin, an orange tabby who came to us scalped. I managed to reattach the skin on top of his head but his ears never grew back. He’s just the sweetest thing but most people are hung up on the idea of their cats having ears.

Riley doesn’t much like Seymour, who has a habit of leaping onto the bed at delicate moments and then discharging his dinner onto the floor. Margin, however, is Riley’s kindred spirit, a reckless tom who always cuts it a little too close. When Riley leaves in the pre-dawn hours, he lets Margin in from his nocturnal adventures. “She’s all yours now,” Riley murmurs to Margin as he passes through the door. I curl up in bed with Margin over my feet and listen to Riley’s car sputter homeward.

Riley likes to barhop, three or four bars an evening. This gets problematic; he won’t leave a drink unfinished. When he decides to leave he just opens his mouth and pours the remaining Guinness down. Guinness after Guinness—he is certainly getting his daily requirement of iron. I leave ciders half-drunk all across town. Riley looks askance at my reckless abandonment of paid-for alcohol but says nothing.

I let Riley drive my car, even though I know he doesn’t have a license – nor a last name that I know of. He says he’s thirty-five but I think that’s a lie. “Anywhere from forty to sixty,” guessed Bobby from behind the bar. Riley never shows me any identification. We keep our contact simple, limited to these nights of pubs and quick-caught pleasure. When he’s had me, he kisses me on the forehead and goes home. I wonder if I want more than that.

The nights I’m not with Riley he calls, after the bars have closed. He and his ragtag group of Irish musicians play a couple of gigs here and there. If he doesn’t invite me along, he always calls me afterwards. I suspect I am his one and only, although I am careful not to mention it. I’ve taken to sleeping with the phone under my pillow so as not to disturb my upstairs neighbors when the phone rings.

“I wish I were a better man,” he confesses drunkenly.

“You could be,” I tell him. He will not remember this phone call in the morning.

“You’re my dream.” Some times Riley sobs into the phone, long, aching, painful sounds. I hold the phone away from my ear.

Riley is mainly a carpenter, although he would rather be a full-time singer. Some evenings he comes over covered with sawdust and sweat. He is already drunk.

“Don’t you take a shower after work?” I ask.

“Of course,” he says offended, “I just stopped off for a quick pint with the boys first.”

I don’t remind him that it is already well after nine-thirty. I pour him a bubble bath, and light the candles and wash his back.

“You’re the best woman I’ve ever met,” he says with a sigh.

I nag Riley about his drinking. He tells me he is afraid he is dying. Sometimes he falls asleep at my house and he stops breathing. I wake him up and give him a lecture about sleep apnea and seeing a doctor. I don’t think Riley has health insurance so I offer to get him an appointment with my friend Donna who’s doing her residency at a local hospital. But Riley won’t go to the doctor. I almost hope Riley has other women; ones who watch him sleep and keep him breathing. At rest, he looks ancient. He has old man neck, a red wrinkled turkey of a neck with sagging folds that shake when he snores. When I’m not distracted by the flashing blue of his Irish eyes he doesn’t seem half as handsome. I grab a book and wait for the moment when he will wake up and with muttered curses, escape my house before daybreak.

I’m not sure how Riley gets the things he has. He has several trucks and a crew of men. He carries a cell phone and a beeper but he doesn’t have a checking account. He’s a real Blanche du Bois, my Riley, depending on the kindness of strangers at every turn.

It turns out that Riley isn’t even Irish. He’s Welsh. I learn this from his friend Fergus, one night at the bar.

“He’s good,” I say to Fergus as we stand by our pints, watching Riley sing and play guitar with more passion than precision.

“Yeah, but it’s a bit of a cheat, him playing the Irish songs and all.”

“Why?”

“He went to Dublin after he was grown. His family owns a horse farm in Wales. His mother’s related to the bleedin’ queen, and here he is pretending to be Irish.”

I look at Fergus and then back at Riley onstage. Riley royalty? It hardly seems possible. His battered visage looks distinctly unprincelike.

That night, Riley doesn’t go home. I enjoy the novelty of sleeping beside him, of showering together and sharing the morning conviviality of tea with the cats curled around our feet.

“I think you are good for me,” he says over toast and jam.

“Perhaps,” I murmur, smiling behind my newspaper.

But then, Riley begins to stop by for lunch sometimes. I clear out my schedule in the middle of the day. We meet at my house and I make us ham sandwiches. Or rather he makes them. I provide the ham and the bread. The first time I slapped one together he ate it, but the next time he insisted on making them for both of us. Riley constructs sandwiches, ham, tomato, mayonnaise, with the crusts off the bread and neatly sliced in half. “Just like Mum used to make,” he proclaims, handing me a sandwich with a flourish.

“Thank you,” I say, marveling at a Riley who is comfortable in daylight, in my kitchen, cheerfully wiping his hands off on a dishtowel. Is it my imagination or does he look healthier?

At the cat shelter in the afternoon, I am comforted by the sameness of the straggly tomcats with their bitten ears and patchy fur. The cats are indistinguishable in their maladies and their yowling complaints. I hold them down on the metal table, patching wounds and checking teeth. I work until well after dark and it doesn’t occur to me until nearly seven that I have a date with Riley in an hour. But Riley has never been punctual, I can always rely on at least a half an hour lag time, that is, if he shows up at all.

Riley arrives exactly at eight o’ clock. He looks suspiciously clean. His shirt is tucked in and, horror of horrors, his socks actually match. I sniff his breath; it’s minty-fresh.

“Riley,” I say, narrowing my eyes, “have you been drinking?”

“No, ma’am, I haven’t.”

“Well, why not?”

“You told me I shouldn’t drink so much, that it’s bad for my voice. I’ve been thinking maybe I should clean up my act.”

“We’re not going out tonight are we?”

“We always go out, I thought it might be nice to stay in and talk and cuddle. Look, I rented a Merchant-Ivory movie.”

That night, I say goodbye to Riley.